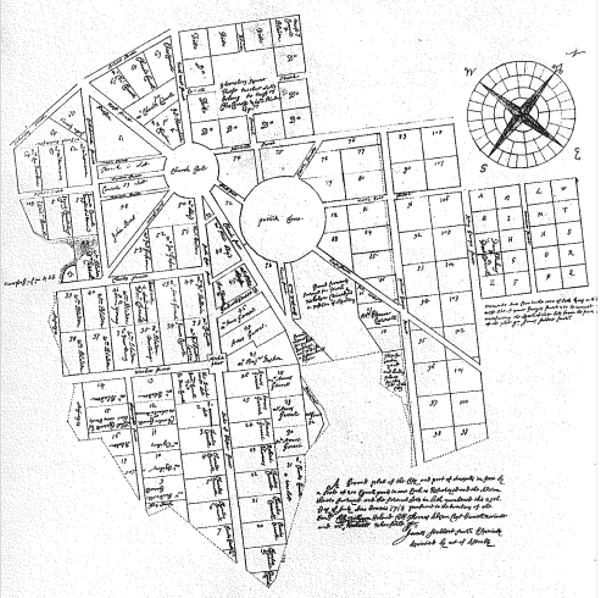

Annapolis City PlanAnnapolis is a unique city. Her combination of four salient features is not found in any other city in America. First, the design of the city is a complex composition of monumental circles with radiating streets superimposed on a regular street grid. Second, the street plan ingeniously engages the topography of the land and the waterfront. Third, while the design aims at monumentality, the scale of the city is intimate and personal. Fourth, the city is over 300 years old, and survives today largely intact. The

city was designed by Francis Nicholson as soon as he was appointed

Governor of the Colony in 1694. The Crown instructed Nicholson to create a

new capital city for the colony, complete with buildings for the seat of

government, the church, a market, and building lots to be sold for homes

and businesses. The new capitol city was funded by establishing that the

import and export of goods could only occur in the ports of Annapolis and

Oxford, on the other shore of the Chesapeake Bay. There were harsh

penalties for not paying import and export duties. Centralization would

allow the efficient collection of taxes, and establish a locus of power.

The Crown needed a new capital city with the monumentality to maintain its

authority in a distant land. When Nicholson went to the site of the new capitol city, there were few or no buildings to be seen. Some previous settlements there were called Proctor’s Landing, Anne Arundel Town, Arundelton and Severn, all failed to last. The main attraction: it had one of the best natural harbors in the area.

Nicholson

was in London for two years prior to his appointment as Maryland Governor.

There he knew the architect Sir Christopher Wren, who designed St.

Paul’s the English Baroque Episcopalian Cathedral (1675-1710). He also

knew the landscape architect John Evelyn, who had developed an innovative

Baroque urban plan for the rebuilding of London after the devastating fire

of 1666. The similarities of Evelyn’s plan for London and Nicholson’s

plan of Annapolis are striking. The oval street around London’s St.

Paul’s has radiating streets superimposed over a regular street grid.

Also of note is that the radiating streets are not precisely symmetrical,

and St. Paul’s is built on the highest ground in London. Baroque

architecture reached its peak in Italy in the mid 1600s. The stylistic

influence of the Baroque is still global and enduring. In France the Dome

des Invalides 1676 by architect Jules Hardouin-Mansart epitomizes the

French baroque, and was the building that inspired the Chapel dome at the

U.S. Naval Academy. Baroque architecture is frequently linked with

European colonization of the period, and used with great effect in South

America in the construction of important churches by the Catholic Church.

It is therefore not surprising that the English Crown would endorse a

Baroque plan for an entire city to be the new capital of their Maryland

colony. Nicholson

fully grasped the London street plan theory. He also had the vision to see

the potential of dynamic Baroque design concepts.

For Annapolis he created a new plan embracing the natural features of the

site, functionally engaging the harbor, and exploiting the dramatic

potential of the high ground. His design created complicated urban

sequences, a rich variety of building sites, street views capturing sights

of the water, and established monumental settings for important

institutional buildings. The

two highest points of land became the centers of Church Circle and State

Circle. Radiating streets set roughly at compass points diagonally cross

the regular street grid. The radiating streets set up the monumental views

toward the Church and State House. The regular streets: Duke of

Glouchester, Prince George, Charles, and Market, all terminate in water

views. The most dramatic of all the streets is Main Street, directly

connecting the harbor with Church Circle. The man made vertical spike of

St. Anne’s Church steeple at the top of Main Street is the counter point

to the natural horizontal line of the horizon over the Chesapeake Bay.

Nicholson created what all artists strive for: the emotional connection of

mortals to nature; of individual to society; and of man to their own

constructs.

Governor

Nicholson created the city plan specifically to establish Annapolis as a

place of tax collection and seat of power for the Crown. Placing the State

House and the Church of England buildings in street circles on the highest

hills was one way to create civic monumentality. Radiating streets

generate impressive approaches to these institutions. The entire

composition commands attention at every level. The sophistication achieved

is unmatched in any other colony. Not until the 1790s, one hundred years

later, in the urban plan of Washington D.C. do we see anything to surpass

it. But

the circles are not perfectly round or precisely oval, and their buildings

are not positioned near the centers. The streets that radiate from the

monumental hilltops do not align with the circle centers. West, South,

East and North Streets are not accurately directed to the compass points,

for which they are named. The street layouts cut awkwardly through

building lots, creating triangular and trapezoidal property lines. These many irregularities and accidents of life have infused Annapolis with the most fascinating of all human frailties: imperfection. In this balanced dichotomy of the monumental with the humble, the city achieves its defining characteristic. It is charming. The

fact that Annapolis survives today is a remarkable accident of history. It

reached its peak of architectural, social and political importance at the

time of the Revolutionary War. By 1800, Baltimore completely eclipsed it.

Had Annapolis continued to develop, all of its wonderful pre-revolutionary

buildings would have been replaced by the rapid economic and technological

growth of the nineteenth century. Annapolis maintained just enough

economic activity as State Capital and home of US Naval Academy to keep it

from sliding into obscurity as did Williamsburg Virginia, also planned by

Francis Nicholson. When Annapolis was “rediscovered” in the 1970’s,

the pressure to tear down and build up anew was met with the timely

emergence of the historic building preservation movement. Looking

at Annapolis today we find: the oldest State House in continuous use; the

Hammond Harwood House, Paca House, Bordley Randall House, three Brice

family homes, Ogle Hall, Chase Lloyd Home, Acton Hall, McDowell Hall,

Upton Scott and Ridout houses. These are hands down the greatest

collection of 18th century grand mansions in America. The

wonderful assortment of 18th, 19th and 20th

century residential and commercial buildings has grown organically around

these mansions. But these individual buildings are not the most important

feature of Annapolis. As was recognized by architect Ernest Flagg in 1905

when he graciously aligned the U.S. Naval Academy campus gates with the

city streets. The most important feature is the city itself. The Baroque

plan married to the natural topography and waterfront creates a rich

variety of urban spatial arrangements that makes this one of the most

sublime places in which to live and work. |