Maryland Governor's HouseThe history of the Maryland

Governor’s House is a long, troubled, winding tale. There is ruinous

abandonment, then demolished grace, followed by enlightened eclecticism,

and finally pale imitation. PART 1: After the Revolutionary War

the ruins and property were confiscated from the British. In 1788 the

building was completed with a third floor, roof and bell tower cupola, and

has been in use by St. John’s College ever since. When we look at

McDowell Hall today, the bottom two thirds is Bladen’s Folly. In the

1788 renovation, Bladen’s two story entertainment space was doubled in

size. Today it is the beautiful Great Hall in McDowell, and is a

spectacular example of an eighteenth century salon.

The

architect of Bladen’s Folly was Simon Duff. As an early

architect/builder, he relied on English “architectural pattern books”

to create his designs. These books depicted the latest “Georgian”

architectural styles, derived from the work of Italian architect Andrea

Palladio. The architect of McDowell Hall was Joseph Clark, who was also

the architect of the State House dome. Clark went beyond imitating style

books to create his designs. The similarities of the State House dome and

McDowell cupola are fascinating. Both have eight sided bases surmounted by

domed cupolas with acorn finials, yet the dramatic difference of

architectural scale and monumentality perfectly fits each building. It is

a remarkable accomplishment for one architect.

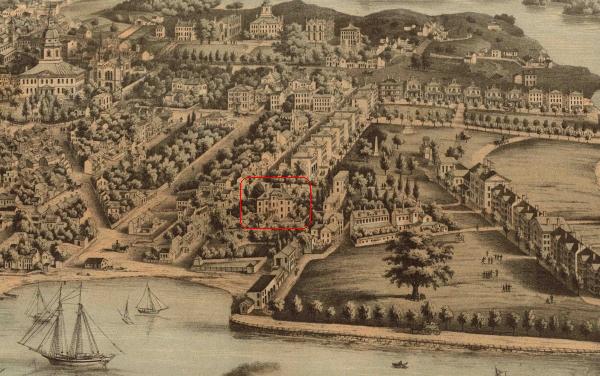

While Bladen’s house was under construction, Edmund Jennings, Secretary of the Province of Maryland and Chief Judge began building his own mansion on land now consumed by the Naval Academy. Jennings had the resources to complete his mansion, which shared striking similarities of size and floor plan to Bladen’s Folly. Both houses featured grand two story entertainment salons. The Jennings house featured a long broad garden sloping down to the mouth of the Severn River as it opens into the Chesapeake Bay. It has been described as a place of great serenity and grandeur.

Edmund

Jennings rented his house to Colonial Governor Horatio Sharp during his

term from 1753 to 1768. When Sharp was replaced by Colonial Governor Thomas Eden

in 1769, the Jennings family sold the house for 1,000 pounds ($150,000 today) to

Governor Eden, who received his appointment by his marriage to the

daughter of Charles Calvert 5Th Lord of Baltimore. A drinker

and gambler, Eden excused himself to England to avoid any unpleasantness

during the Revolution. The house and property were confiscated after the

Revolution to become the first official residence of the Governor of the

State of Maryland. It continued to serve as the official residence until

1869, hosting many U.S. presidents and world dignitaries. The

Naval Academy was established in 1845 to the east flank of the

governor’s house. During the Civil War the Naval Academy moved to

Newport, Rhode Island. After the war, there were rumors that the Academy would not

return to Annapolis. Political pressure in Maryland to “recapture” the

Academy must have been intense. The

Governor’s house and property was viewed by the Academy as an obstacle

in expanding the campus back toward the city. In 1869, the State sold the

property to the Academy for $25,000 ($410,000 today). Incorporated into

the Academy’s post Civil War expansion, it was heavily modified,

enlarged and finally demolished in 1901. Today in front of the

Superintendent’s quarters you can only stand in the street where George

Washington once slept in the governor’s house.

The demolition of the first official governor’s house by the Naval Academy was a great loss to the State. To make up for the loss, the legislature moved to create a meaningful replacement worthy of the admiration of the citizens of Maryland. PART

2:

The

design was certainly of the moment and an expression that after the Civil

War, Maryland was ready to play on the world stage. Andrews created a

building composition that we now call eclectic, but at the time was about

celebrating a broad world view. The spirit of eclecticism was to engage in

the variety of human cultures, an interest in foreign lands, ancient

peoples, and exotic thoughts. This movement reached it pinnacle during the

aesthetic movement of the 1890’s by Tiffany design studios in New York.

The home was lavishly detailed with French Second Empire Mansard roof,

Italianate bracketed cornice, Egyptian stone porch, and among many lavish

interior appointments, a curving Renaissance Revival interior staircase.

This home was a fully considered work of art, skillfully combining a

complex array of eclectic images for the purpose of establishing a multi

sensory setting. The house was fully integrated with interior furnishings

and appointments that aroused exotic interests. It was a house that was

built for its time. Unfortunately

by the 1930’s this eclecticism was viewed as a dated relic of previous

generations. What surfaced in the 1930’s was interest in the generations

of early Americans. Colonial Williamsburg was “discovered” as if an

American Pompeii, and reconstructed like a Disneyland to proclaim the

glory of early Americana. In

the midst of this “early American” hysteria, tragedy struck in

Annapolis: it was conceived that the Governor’s house should be

converted into a “colonial” house. It is so odd that this should

happen in Annapolis, where the collection of genuine unaltered 18th

century architectural masterpieces exceeds any other American city,

including Williamsburg. Architect Clyde M. Fritz had just finished the exceptionally progressive Enoch Pratt Free Library across the street from Benjamin Latrobe’s magnificent Cathedral in Baltimore. But when asked to make the governor’s house colonial, Fritz could only make the best of a bad concept. As the cost of the conversion swelled from $75,000 to $136,000 ($2,137,000 today), the request for additional funds by Governor Harry W. Nice was met by opposition from Representative William H. Labrot, who knew something about architecture. He lived in one of the most beautiful colonial revival homes, Holly Beach Farm, just east of Annapolis designed by Baltimore architects Parker, Thomas and Rice. Labrot said “I do not think the money is being spent wisely… the mansion will not be colonial in architecture… I do not know what style it will be.” When we look at the house today, we see the formulaic trappings of Annapolis 18th century grand houses: steep pitch roof with bookend chimney slabs, a Palladian window lifted out of the Chase Lloyd House floats isolated above an uninspired copy of the Hammond Harwood House front door. The building scale and silhouette is pumped up to a proportion that is a boorish exaggeration of any real colonial house.

Annapolis

lost two important architectural accomplishments in the first two

Governor’s mansions. The Jennings house had achieved grandeur,

graciousness, and monumentality without being overreaching, crass or

pretentious. The 1869 governor’s mansion achieved a harmonious balance

of disparate parts, and created an environment extolling the wonders of

human culture. The mansion of today is a pale imitation of the real

architectural heritage of Annapolis. The 1936 renovation attempt to create

history had the opposite result of destroying history, and sullying the

genuine architectural treasures of 18th century Annapolis. We

cannot let the pressures of current fashion or political expediency

destroy the accomplishments of our ancestors. We should restore and

preserve them. More importantly, we must create new architecture that

speaks of our time, and not artificially attempt to recreate the past. |

Views of the current Maryland Governor's

House:

Views of

|