Annapolis Post OfficeOne

of the most beautiful buildings in Annapolis is on the corner of Church

Circle and Northwest Street. The United States Post Office was designed in

1901 by the United States Treasury Department. James

Knox Taylor was the Supervising Architect of the Treasury at the time, and

made a deliberate effort to build federal buildings that would make

lasting contributions to small towns. Clearly this building does more than

simply provide basic shelter.

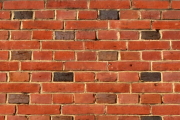

The

architect skillfully blends classical design with architectural elements

found specifically in Annapolis. The goal of this composition is

architectural balance and harmony, while using materials and forms

familiar to Annapolis. There is just enough monumentality in the design to

let you know it is an important building. The monumentality never

over-reaches to grandeur, mostly because of the use of brick, a building

material strongly associated with Annapolis. The

brick used at the Post Office is laid in an alternating header bond

pattern. That is, every other horizontal course shows the narrow end of

the brick to the street. Superimposed on this is another pattern: the dark

burnt brick ends that are laid in a chevron design. This causes a strong

crisscross pattern that floats across the front of the brick wall. The use

of burnt bricks in decorative wall design is a Maryland masonry tradition

dating to the 1600’s. There is a fragment of burnt brick chevron design

on the rear of the James Brice house, on the corner of Prince George and

East Streets.

The

three round arch windows are another familiar Annapolis architectural

form. These can be seen right across the street at Saint Anne’s Church

(1859). Flanking the three round arches are two blind arches with inset

windows. Blind arches are arches with brick infill, as seen in the Church

apse, facing the Governor’s house.

There

are two other classical architectural forms used at the Post Office that

are found throughout Annapolis: one is the use of quoins at the corner of

the brick walls, and the other is the belt course. In the Post Office

these are made of limestone. The corner quoins give the building a

vertical element. The belt course at the bottom of the second floor window

sills provides a subtle horizontal line. Corner quoins are used as St.

John's College McDowell Hall (1744). Brick belt courses can be found on

brick buildings around the city, mostly on buildings of the late 1700s. One of the

most interesting designs of the Post Office is where the belt course

intersects the corner quoins. At this intersection the architect has

created a unique stone shape that has an inverted pan face. This piece

allows the vertical corner quoins to cross the horizontal belt course in a

wonderfully harmonious way. The quoins and the belt course share the same

space without conflict, achieving balance and harmony. Notice the way the

brick wall patterns knit into the stone quoins. The visual effect is

vibrant and complex, but the result is orderly and resolute.

The

craft and workmanship of the Post office is outstanding. The tooling of

the limestone base is very subtle. Around the three arched windows, the

decorative limestone pieces are expertly carved. The two garlands that flank the second floor

center window are a three dimensional stone carving extravaganza. They

float on the wall with no visible means of support. The blue slate “damp course” where

the grass meets the building is used to protect the limestone base from

wicking up soil moisture. This protects the soft porous limestone from

deterioration. Today the stone and brick are as fresh as the day they were

built. The interior wood work

and finishes are all beautifully executed, especially the staircase in the

side vestibule.

When the Post Office was built, two grand important Annapolis houses were demolished. Early photographic views show substantive homes, as one would expect to find in such a prominent location. Unfortunately, their demolition was just the start of the destruction of the entire area defined now by Northwest, Church Circle, Bladen, and Calvert Streets. This area included Bloomsbury Square, a feature of the original city plan designed by Sir Francis Nicholson in 1695, which included a number of homes of free African Americans. The beauty of the Post Office was followed in short order by beastly bland pseudo-colonial state office buildings. Occupying what were previously many city blocks, these buildings have none of the architectural interest, none of the creativity, none of the craft of the Post Office. The most marked contrast between the Post Office and the state office buildings is the way they engage the sidewalk. The Post Office is warm, inviting and encourages participation. The state office buildings turn away from the sidewalk. The James Senate Office Building (1939) next door is the most noble of all of the state office buildings. Unfortunately it has just suffered an ignoble insult: the front entrance door on College Avenue has been locked to public access. The state office buildings continue their march toward an isolated insular campus. The

Post Office survives… for a while. The canopy over the front door sags;

the columns of the cupola are split open, eviscerated by neglect, the

garlands around the cupola are falling off. The Annapolis Post Office is looking for

a new home, they just want a shelter this time… nothing fancy. |

|